The overall goal of Donau Soja is a sustainable, safe and European protein supply

The development of soya production in Europe is part of a wider change in how we produce and use protein. The far-reaching consequences of protein production and use are now the subject of public debate.

Building on the Europe Soya Declaration, Donau Soja has developed the Donau Soja Protein Strategy as a means of contributing to the public debate on behalf of all its members. The strategy builds on a holistic and science-based understanding of the role of protein in the sustainable development of agri-food systems.

The Donau Soja Science Advisory Board was consulted on the first draft before it was considered by the Donau Soja Board. The Board then issued a revised draft which was sent to all the members who were invited to comment.

All the comments were considered during the finalisation of the document, and the strategy was unanimously passed by the General Assembly of Donau Soja in April 2018.

The strategy is therefore a powerful statement from the agri-food sector, as represented by Donau Soja, about their commitment to support profound change.

THE EUROPEAN PROTEIN CHALLENGE

–

Due to the nature of the climate and soil, many farmers in Europe are remarkably good at growing cereal crops such as wheat, barley and maize. This supports the production of large volumes of carbohydrate-rich grains which are mostly fed to livestock.

The European Union’s productive agricultural system relies on two major inputs: around 11 million tonnes of synthetic nitrogen fertiliser for crops, and high-protein meal, made from around 36 million tonnes of soybeans, as a protein supplement used to feed animals. The increase in European demand for plant protein over the last 60 years is largely due to the increased production and consumption of meat and dairy products.

After China, the European Union is now the second largest importer of soya from South America. While the European Union’s agricultural system as a whole is 71% self-sufficient in tradable plant protein, 86% of the plant protein which is imported to meet the 29% deficit is soya.

This protein deficit is a fundamental challenge to the resilience, acceptance and performance of our agri-food systems. This is Europe’s Protein Challenge.

Addressing the protein challenge

–

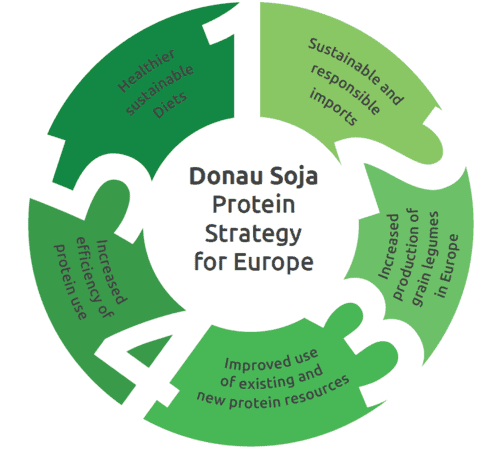

A holistic approach is needed to address the Protein Challenge and deliver the Protein Transition. The system change this requires can be viewed as a set of five pillars:

Display none

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

Sustainable and responsible imports

The Protein Challenge is global. Although is vital that Europe leads this system change, we need China at our side. Even with a significant agricultural shift, Europe is still likely to need to import plant protein from traditional exporting regions. However, we must switch to importing certified products from regions and systems which are thoroughly validated according to stringent environmental and social standards. We must also collaborate closely with China to ensure a global shift towards more sustainable protein production. It is our current farming and food systems which have the greatest impact on the nitrogen cycle. The production and consumption of protein are major drivers of greenhouse gas emissions. Nitrate and ammonia pollution in the air and water, paired with a loss of natural habitats and biodiversity, can only be addressed by a global shift to more sustainable protein production, achieved by meeting responsible production and trade standards. It is here that Europe and China can work together to drive global change.

Increased production of grain legumes in Europe

We forfeit many agronomic benefits and environmental advantages because of low levels of legume planting. Increasing grain legume production in Europe will bring a wide range of advantages and reduce the protein deficit. In Europe in particular, grain legumes will increase crop diversity and support pollinating insects. Nitrogen fertiliser is unnecessary as legumes absorb nitrogen from the air. They counter the build-up of disease, pests and weeds in cereal-based crop rotations by being biologically very different to cereals. Overall, a general lack of crop diversity is associated with stagnation in crop yields and higher costs, as our primary crops succumb to more weeds, pests and diseases. European farmers can respond to the increased demand for plant protein produced in Europe to high environmental and social standards, and simultaneously meet the growing demand for non-GMO products and regional/local value chains. The industry can collectively set standards for all protein sources and signal support for sustainable production. The greatest potential for improving cropping systems using grain legumes lies in Central and Eastern Europe. As a result, transatlantic trade would be partly replaced by east-to-west sourcing within Europe, helping to reduce social and economic disparities within the EU, and encourage regional development in what are currently deprived rural areas. In western Europe there is also potential to increase grain legume production without displacing cereal and oilseed production, due to the yield benefits of crop rotations.

Improved use of existing and new protein resources

Plants are by far the most important primary source of protein. While co-products such as rapeseed meal, sunflower seed meal and distillers’ dried grains are already used by the feed industry, there remain opportunities for better use of agri-food residues in livestock feeding. Additionally, in many areas of Europe our grassland-based production systems could make better use of grass and high-protein grassland species such as clover (a legume) to reduce soya use. Forage crops such as alfalfa are also protein sources. There are also potential opportunities for protein production in fields such as algae culture.

Increased efficiency of protein use

Better matching of livestock diets to livestock protein requirements saves protein and reduces pollution by reducing the excretion of nitrogen compounds. This can make a significant contribution to farmers’ compliance with nutrient balance-based fertiliser management systems. Protein is usually an expensive component of feeds, hence more precise feeding can also reduce production costs.

Healthier and more sustainable diets

The scope of the European Protein Challenge is largely determined by the quantity of livestock products which are consumed and produced. Human diets which rely more on plant-based protein, especially pulses and soya, are healthier and more sustainable compared to the typical diet of EU consumers today. A large proportion of the population consumes more meat and dairy products than recommended for a healthy diet. This has far-reaching consequences because it requires a large livestock sector. Most of the nitrogen in the plant protein consumed by these livestock is excreted and is the primary cause of agricultural pollution of the air and water. The environmental impact is particularly significant where livestock production is regionally concentrated. Reducing the consumption of animal products to a reasonable level, with a corresponding reduction in livestock production, would improve the performance of our agri-food system in terms of human health, the environment and land use.

Find more information from the European Plant-Based Foods Association, ENSA here